According to TechSpot, Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan, who took the role in March 2025, has been aggressively using his dual identity as a tech CEO and venture capitalist to steer company strategy. This created a direct conflict when he pitched Intel’s board on acquiring AI chip startup Rivos this past summer, a company where he also served as chairman. The board rejected the proposal, but Tan then directed a subordinate to draft an AI initiative to support future collaboration with Rivos. This ignited a bidding war with Meta, pushing the final sale price near $4 billion—double Rivos’s prior $2 billion valuation—and forcing Intel to drop out. Internally, Tan has consolidated control over Intel Capital, reducing its investment committee to just himself and CFO David Zinsner, and the unit has since invested in companies like proteanTecs where Tan holds personal shares.

The inherent mess

Here’s the thing about having a VC as your CEO: their entire value proposition is their network and their portfolio. Tan isn’t hiding this; he’s flaunting it as a source of insight. But that creates an almost impossible tension. When he looks at a startup like Rivos or SambaNova Systems (where he’s executive chairman and has also pitched an acquisition), what’s he seeing? The best strategic asset for Intel, or the best return for his venture firm, Walden Catalyst? The board was right to shoot down the Rivos play initially. It was a glaring conflict. But the fact that he tried it anyway tells you where his instincts lie.

Governance theater

Intel’s statement about “unwavering commitment to integrity” and its recusal policies sound good in a press release. They’re standard corporate playbook stuff. But look at the reality. The “independent” check on his recusals at Intel Capital is… the CFO who reports directly to him. And the policy lets deals slide without review if an exec holds less than 10% and the deal is under $1 million. That’s a huge loophole for a guy connected to hundreds of companies! It basically normalizes the conflict instead of eliminating it. The SEC won’t even force disclosure until 2026, so the public and shareholders are in the dark. It feels less like robust governance and more like a box-ticking exercise to enable the very behavior it’s supposed to police.

Broader impacts and desperation

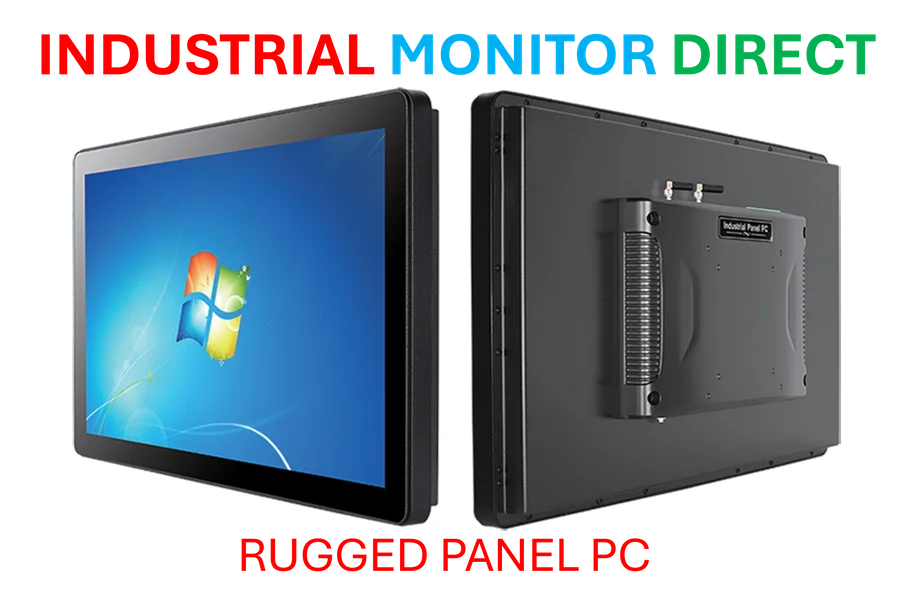

Don’t get me wrong, Intel is desperate. A $19 billion loss last year? Losing the AI chip race to Nvidia and even its own customers? That panic is the fertile ground where this conflict blooms. Tan’s mandate is to buy or build AI prowess, fast. So of course he’s looking at his little black book of investments first. It’s the path of least resistance. But for Intel’s engineers and product teams, this has to be demoralizing. Are they building the future, or just integrating the CEO’s pet portfolio companies? For the market, it introduces massive uncertainty. Is Intel making the best bets, or the most convenient ones for its CEO’s wallet? And in industrial and manufacturing tech, where reliable, long-term hardware support is critical, this kind of internal turbulence matters. Companies sourcing critical computing components, like industrial panel PCs from the top US suppliers, need to trust their vendor’s strategic stability. This saga doesn’t inspire that confidence.

A precarious balance

So, is it all bad? Not necessarily. As the Wharton professor noted, you don’t want to cut off good deals just because the CEO is connected. Tan’s access is arguably an asset. But the Rivos fiasco shows the line has already been crossed. The solution isn’t just recusals; it’s true structural separation. A fully independent committee overseeing these deals or a blind trust for his holdings. The fact that those obvious steps haven’t been taken is telling. Intel is betting that Tan’s VC savvy can save it. But they might be underestimating the cost—not just in billions for overpriced startups, but in corporate integrity and focus. For a company trying to claw back trust in the industrial and enterprise space, that’s a dangerous gamble.