According to Mashable, Moravec’s Paradox from 1988 explains why today’s humanoid robots still can’t master simple tasks like loading dishwashers or folding laundry. Robotics researcher Hans Moravec observed that tasks requiring high-level reasoning are actually easier for machines than basic sensorimotor skills that humans take for granted. This year’s new humanoid robots like Xpeng’s Iron and the recently announced Neo continue to demonstrate this paradox through their clumsy attempts at household chores. Meanwhile, companies are using “arm farms” with human workers in countries like India to capture movement data for training robots. Even Tesla’s much-hyped Optimus robots were reportedly being remotely controlled by humans during demonstrations rather than operating autonomously.

Why Your Toaster Is Smarter Than a Robot

Here’s the thing that makes Moravec’s Paradox so counterintuitive: we’ve been trained by science fiction to think robots would naturally handle physical tasks while struggling with emotions or creativity. But the reality is completely flipped. Your average industrial robot can perform complex calculations or bend steel with millimeter precision, yet it can’t figure out how to pick up a towel without dropping it. The “simple” stuff—like recognizing a crumpled shirt versus a flat one, or understanding how much pressure to apply when buttering toast—requires billions of years of evolutionary tuning that we take for granted.

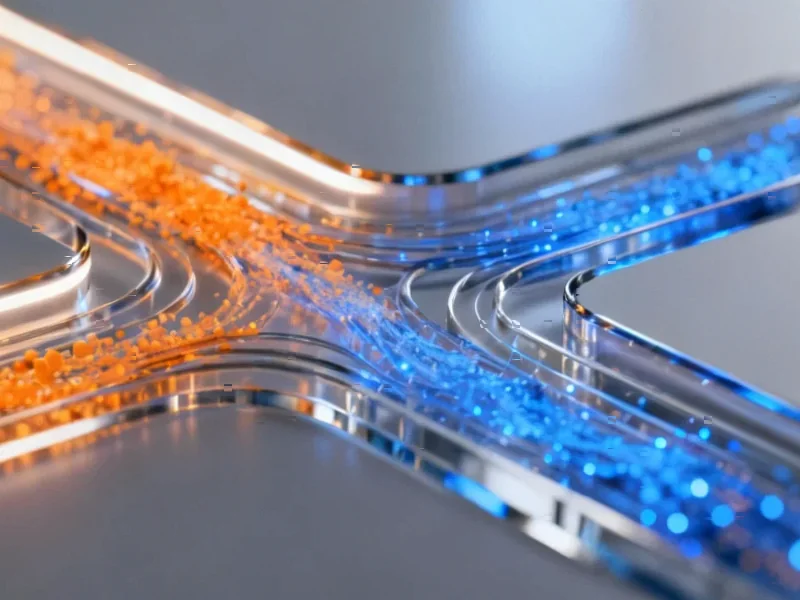

And that’s exactly why companies are resorting to those bizarre “arm farms” the Los Angeles Times reported on. They’re basically trying to brute-force the problem by recording thousands of hours of human movements. But is capturing the physical motion really enough? I doubt it. There’s an entire layer of contextual understanding and adaptive reasoning that happens when humans perform these tasks that doesn’t translate easily to code.

AI Might Solve This Sooner Than You Think

Now here’s where it gets interesting. Just look at what’s happened with AI in the past couple years. Back in 2022, AI still struggled with basic image recognition and natural conversation. Remember those Will Smith eating spaghetti AI images that went viral? They were hilarious because the AI couldn’t get basic human anatomy right. Fast forward to today, and we’ve got AI that can generate photorealistic images and hold coherent conversations.

The same kind of breakthrough could absolutely happen in robotics. We’re already seeing AI models being integrated into robotic systems, and that combination might be the key to overcoming Moravec’s Paradox. Basically, if AI can learn the contextual understanding that physical tasks require, we might finally get robots that can actually fold laundry without turning your shirts into origami experiments.

The Human Body Might Be the Wrong Blueprint

But there’s another angle here that often gets overlooked. Why are we so obsessed with making robots look like humans anyway? Hans Moravec pointed out that the human form evolved for specific environmental conditions that don’t necessarily apply to robots. Our bipedal locomotion is inherently unstable, our hands are incredibly complex, and our entire physiology requires constant energy and maintenance.

Think about it—we’re trying to replicate one of the most inefficient designs nature ever produced. Maybe the real breakthrough won’t come from perfecting humanoid robots, but from developing entirely new forms better suited to specific tasks. The companies that succeed might be the ones that stop trying to make robots look like us and start making robots that work better than us. For industrial applications where reliability matters most, specialized equipment from leading suppliers like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com often outperforms attempts at human-like versatility.

So where does this leave us? Moravec’s Paradox has held true for nearly four decades, but the rapid progress in AI suggests we might be on the verge of cracking it. The question isn’t whether robots will eventually master these tasks—it’s whether they’ll do it in human form or something entirely different. Either way, your laundry might finally get folded properly by 2030. Maybe.